With this publication, IUSS tells its story. Some teachers and key figures in the school have chosen to share their vision of the future here, providing a glimpse into the world that awaits us. This window is wide open by those who have chosen to embark on the adventure of their lives with a telescope focused on one of the infinite aspects of knowledge – knowledge aimed at improving the human condition. Like a kaleidoscope, you will find a different perspective on every page, and if you are curious to delve deeper, by scanning the QR code, you can read the rest of the story and get to know the author. Enjoy your reading!

«Will I manage? Will I succeed?"

You must have asked yourself that many times when faced with a great challenge. You must have tried to weigh your skills and experiences, but perhaps most of all, the confidence in your possibilities. Faced with an elusive future, you must have thought of those who preceded you, you must have entrusted yourself to the gaze of the people who had the same doubts and took risks before you did. They had faith. They did not pre-package any solution. They bet on the success of a worthy project.

Sometimes it went well. Other times, not quite. But from that, they learned that mistakes, attempts, experiments, and hypotheses animate the process of any discovery: in laboratories, in university classrooms, in life.

IUSS academics talk about themselves to share the outcome of their experience with you, to talk about the contamination and multidisciplinarity of knowledge, the processes of discovery and growth through which a better world can be built. Today they will be the ones to guide you through the discovery of your own path!

THE IUSS SCHOOL OF PAVIA

IUSS University School is characterized by three founding and supportive elements, none of which can be truly effective without the others, despite having independent natures and purposes. The supra-disciplinary vision of reality: the disciplines are the foundation and methodological basis of the investigation of reality, but do not characterize the purpose of the study, and their task is to provide the tools for solving problems rather than creating alternative general visions; the substantial contiguity between teaching and research, which necessarily shifts the former towards cutting-edge themes in which the School's academics are chosen among the protagonists on an international level; the relationship of personal trust between academics and students in a training environment, that of Pavia, characterized by the historical presence of the University of Pavia and colleges of merit. In this sense, the School, which, for its first levels of study, draws from the selective pool of this system, responds to the original mission of modern higher education, which must, among other things, give back to society the resources that society has dedicated to it, and it must provide a unique opportunity for expression and governance to people who otherwise would not have access to these levels. A unique presence in Lombardy, the School is open and attended by students from all over the country and, on a doctoral level, from all over the world.

THE REVOLUTION OF THE SOURCES

ANDREA MORO Vice-Rector

"Understanding does not mean building from scratch but selecting from the overabundance of possible structures the only ones that are compatible with reality. We imitate nature”.

Real cultural changes are often imperceptible, very slow and rare. There are, however, instances where suddenly everything radically changes: one example was the invention of the printing press. In the space of a few years, access to knowledge was unleashed from the production of individual texts, and the available sources multiplied to an unimaginable quantity compared to previous eras. Today, we are eyewitnesses to a change of no less magnitude than this, the influence of which has far-reaching consequences on everything in the world of culture, research and education and, if the analysis I present is correct, on the entire social fabric.

It is not difficult to grasp this paradigm shift: for the first time in the history of our species, not only of Western civilisation, which is often taken as an absolute reference, it is no longer the difficulty of finding information that characterises a central aspect of scientific research and, more generally, of education, but that of learning to select from the mass of accessible information the (few) relevant ones. In a networked world, we move from the art of collecting to that of discarding.

While it is true that this discontinuity in the progress of knowledge, which without negative connotations epistemologists would call, referring to its etymology, a catastrophe, is evident to all, it is not at all immediate, at least to the writer, to recognise what its consequences are. There are many, both technologically and politically and ethically, but there is one, perhaps more hidden than others, that is worth emphasising here precisely because it concerns both protagonists of the learning dynamic: teachers and learners.

Sources must be selected for at least two reasons: first, because reading all sources would take too much time and too many resources compared to the propositional part of the projects; second, because it is never, in fact, possible for all sources to be correct and consistent with each other. The second aspect, of course, is part of the canonical role of the researcher and consists of the obligation to take a position with respect to previous opinions, whether they are oppositions, total agreement or intermediate positions. But it is the first factor, perhaps seemingly trivial, that actually forces the real change. If it is true that in the presence of endless sources, there is no point in reading everything before starting, then there is only one way to proceed: trusting someone who has already done so in part before us.

This is the new, unexpected, unpredictable paradigm shift on the social level that the new situation with respect to sources imposes on us. If we do not want paralysis and still want to progress, we cannot but pass through an act of trust in people who, for different reasons, have already done part of the selection process. The new learner is the one who recognises this situation and, by virtue of an explicit choice (at least to themself), frees themselves; that is to say, they entrust themselves to a person who, at that moment, literally replaces them in the choice of whom to listen to. A figure that, with terms that would certainly need updating, should they be interpreted in the connotation of gender, we would call a 'teacher'.

That the human factor emerges precisely from the new technological conditions also seems to me a truly extraordinary and unexpected fact. The transition from collecting to discarding cannot be made alone: it must pass through a human relationship of trust that necessarily influences the project. It must be explicit and precise.

True trust is placed not in those who are expected to make the choice we want but in those who are expected to act for our good, whatever choice they make. Trust is a blank proxy for the personal good, and while it is true that many people can recognise it in so many areas of life and many relationships, finding it inextricably intertwined with the scientific method is a truly astonishing fact not to be overlooked.

A second effect, perhaps less obvious, is that the increase in the number of possible connections between sources facilitates the dismantling of that epistemological wall that, although decisive in progress since the Renaissance, namely the distinction between the humanistic and the scientific, has now become an encumbrance. The new Renaissance will only develop where a new global reading of reality can be grasped where objects, ends and methods are not claimed by ideology or authority but are commensurate with the ability to solve new problems. In this sense, today, the encyclopaedic model seems to be much more pertinent to research than the watertight compartmentalised model of the disciplines on which, all too often, academic fences have been modelled in recent times.

A note in closing, equally unexpected: the model of knowledge based on selection among sources is actually the one that comes closest to the neurobiological models of human learning, those that, starting with the language learning revolution proposed by Noam Chomsky in the second half of the 20th century, led to the realisation that understanding does not mean building from scratch but selecting from the overabundance of possible structures the only ones that are compatible with reality. We imitate nature.

Find out who is Professor Andrea Moro

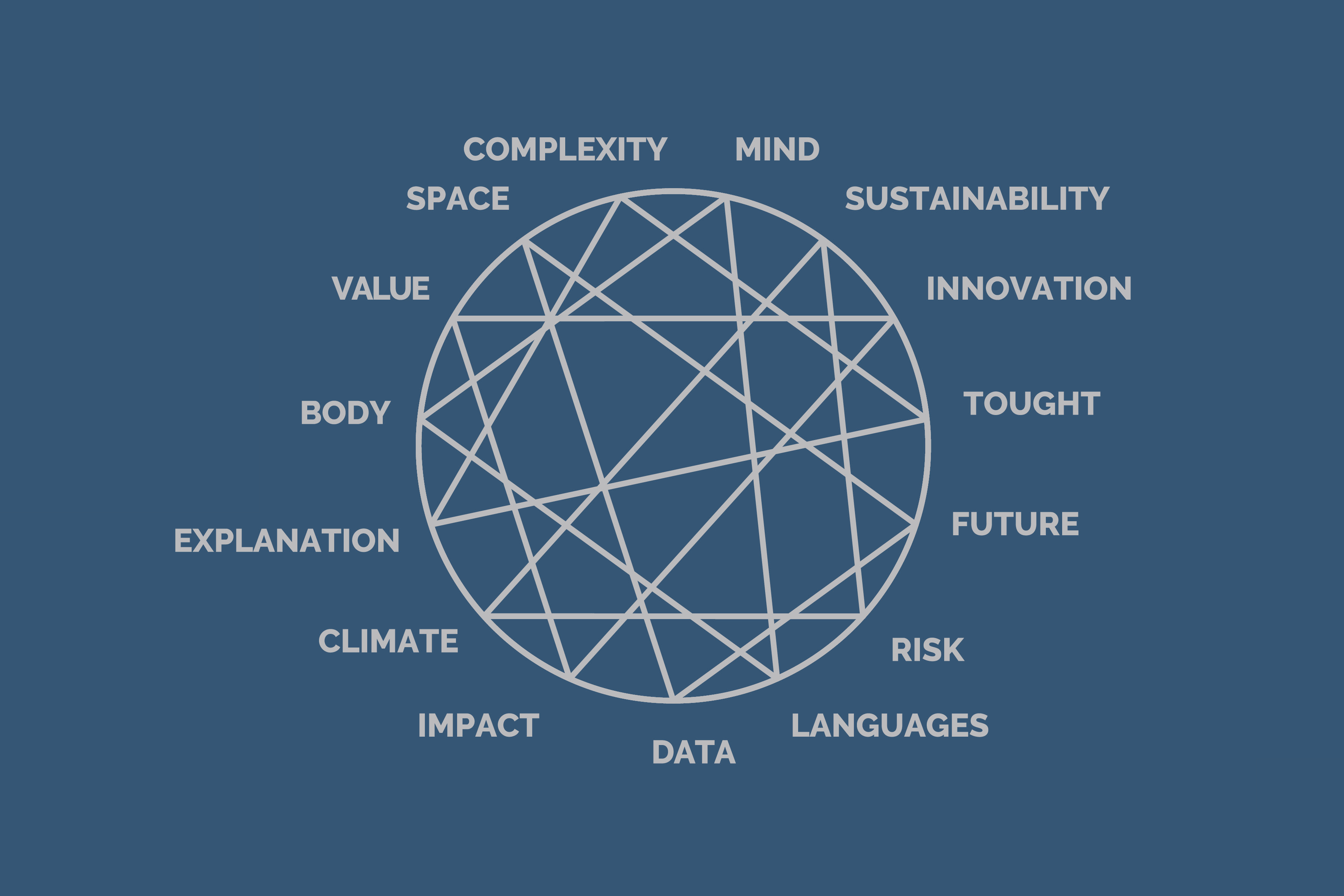

IUSS University School of Pavia has always based its uniqueness and its philosophy of transmitting knowledge on the interaction between disciplines, languages, people and worlds. The identity of IUSS, which is well represented by the Nexus logo, is made up of a network of connections, of relationships between people, themes and problems, that the School recognizes as distinctive and which characterize its research and teaching. Not scientific sectors separated by disciplinary fences but themes and paths, common visions, an expression of those who, from their different experiences training, have developed a different perspective on the world.

THE RESEARCH I LONG FOR

VALENTINA BAMBINI Linguist, ERC winner

“Behind both the technological and cultural progress of societies there is the passion of women and men who, moved by curiosity for the world, decide to dedicate their lives to research”.

Behind the ultra-thin and ultra-performing computers of the future is graphene research; behind innovative multilingual education programmes are years of studies on the effects of bilingualism, no longer seen as an obstacle to learning; behind the latest organic personal care product is research on sustainable surfactants that do not harm the marine ecosystem. In short, behind both the technological and cultural progress of societies there is the passion of women and men who, moved by curiosity for the world, decide to dedicate their lives to 'research', delving into problems, finding answers, creating new solutions.

But passion is not enough. Passion alone would not be enough to make research different from a hobby. The other fundamental element is the scientific method. A method that stems from the in-depth study of the state of knowledge, the formulation of hypotheses and counter-hypotheses, the close comparison with empirical data, and openness to innovative approaches from related fields. The Nobel Prize in Medicine went to Rita Levi Montalcini in 1986, after thirty years of exploring nerve growth factors. The portrait of Dante that we can now admire in its renewed vividness at the Uffizi Galleries results from in-depth investigations not only into the history of the fresco but also into its state of preservation and the materials that make it up. The complexity of today's world requires a rigorous method capable of considering a large amount of information and integrating approaches from different disciplines. The research I long for is open to multidisciplinarity, promotes teamwork, and faces new challenges without prejudice, while maintaining the compass of scientific rigour.

Research is behind every aspect of technological and cultural progress – so we said. Yet, if we were to take a survey and stop passers-by in the street and ask them how they imagine a researcher, a rather limited picture of research would emerge. Most people would describe a figure in a lab coat, tinkering with ampoules to produce a new drug. A large part of our research is not understood by society. When describing my studies on language and metaphors, I receive questions such as: "Are you speech therapists?", "Are you neurologists?".

Identifying unfamiliarity with academic disciplines as the cause would be too easy. Researchers must improve their ability to reach out to society as a whole. And this is all the more so when we consider that around 30 per cent of research is directly financed by the money of our fellow citizens.

The research I long for is capable of maintaining a dialogue with society, taking its demands on board, and becoming 'participatory'.

At IUSS, in our courses, not only do we try to transfer ideas but teach the method of research, contaminating disciplines, illustrating strategies for the exploitation of results in society, and bringing young minds to the heart of what is, in our opinion, the most beautiful profession in the world.

Find out who is Prof.ssa Valentina Bambini

THE BRIDGES I LONG FOR

GIAN MICHELE CALVI, Structural engineer

“Imagine London, Paris and Rome without dry paths across the Thames, the Seine and the Tiber...”

Imagine all the people ... Livin' life in peace ...

In 1971 John Lennon (inspired by Forrest Gump, as everyone knows) imagined a different world.

A few words that everyone could dream up as he wished.

Unlike John Lennon, few people know Henry Petrovski. Twenty years later, he too imagined a different world, but his dream became a nightmare.

Imagine a world without bridges.

Imagine London, Paris and Rome without dry paths across the Thames, the Seine and the Tiber.

Imagine Manhattan as an island with no hard crossing of the Hudson and East rivers. [...]

Imagine Florence with its Uffizi and its Pitti Palace but without their connection across the Ponte Vecchio ...[1]

A world with the Creation, but without the works in which man has left his mark.

The Romans built magnificent bridges, to move armies, like Caesar[2] across the Rhine, but also to carry water to unimaginable distances, like the Pont du Gard in Nimes. Caesar's bridge lasted less than his army. The one over the Gard continues to testify to the construction wisdom of Roman engineers.

I long for bridges that span many generations.

Herodotus tells of Xerxes crossing the Hellespont on a pontoon bridge. The Dardanelles Bridge (Çanakkale Boğazı Köprüsü), with the longest span in the world, was built in that same place.

Thus, starting from Abydos in the direction of this stretch of coast, they built the bridges according to orders, the Phoenicians with white linen ropes, the Egyptians with papyrus ropes. There are seven stages from Abydos to the opposite[3]coast .

Thucydides tells of the war between Athens and Sparta, with the fleets facing each other at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth. A bridge was built there, inaugurated in 2004 by the passing of the Olympic torch.

This cape, Rio, was a territory linked to the Athenians by bonds of friendship: the other Rio, which is part of the Peloponnese, is situated on the opposite bank. The distance between the two points is about seven stadia, naturally by sea: it is the mouth of the gulf of Corinth[4].

I long for bridges that tell the great stories of the past.

In 1891, an elegant swing bridge was inaugurated between La Maddalena and Caprera. You can see it in some old postcards. It was later replaced by two Bailey truss bridges, functional but hideous.

In 2009 a new bridge took over the old one, with 21st century technologies and materials. Crossing it feels like walking on water, calm on one side, rough on the other.

I long for elegant and functional bridges that dream and make people dream.

Bridges have become symbols and souls of cities, and each city's bridges have been shaped by, and in turn, shape the character of that city. [...] Imagine the Golden Gate spanned by anything but the Golden Gate Bridge. Is it possible?1

I long for perfect bridges, which narrate the glory of God through the work of man.

Marco Polo describes a bridge, stone by stone.

– But what is the stone that supports the bridge? – asks Kublai Khan .

– The bridge is not supported by this or that stone, – replies Marco, – but by the line of the arch they form.

Kublai Khan remains silent, reflecting. Then he adds: – Why are you telling me about the stones? Only the arch matters to me.”

Polo replies: “Without stones, there is no arch” [5].

At IUSS we talk about the arch, but also about the stones.

[1] H. Petrovski, Engineers of dreams. Great bridge builders and the spanning of America (1995). Knopf.

[2] G. J. Caesar, Commentarii de bello gallico (58-49 a.C.). IV, 17.

[3] Ἡρόδοτος (Erodoto), Ἱστορίαι (Storie, ~430 a.C.). VII, 34.

[4] Θουκυδίδης (Tucidide), Περὶ τοῦ Πελοποννησίου πoλέμου (La guerra del Peloponneso, ~410 a.C.). II, 86.

[5] I. Calvino, Le città invisibili (1972). Einaudi.

Find out who is Prof. Gian Michele Calvi

THE DECISIONS I LONG FOR

NICOLA CANESSA, Psychologist

“It is only in a sufficiently broad time horizon, and not in the short-sightedness delivered to us by the news, that a path which is punctuated by failures as well, can lead to a few, yet great, elevant, successes”.

In a phrase that later became an aphorism, chemist and physicist Jean Perrin, Nobel Prize winner for Physics in 1926, stated that “explaining the complex visible by some simple invisible” is that form of intuitive intelligence that guides scientific advancements. A path that researchers know requires constant effort, only sometimes rewarded by accomplishments granting the pleasure of discovery, the awareness of having expanded the boundaries of knowledge, and the hope for the positive effects of this contribution. Carrying out research in the field of decision-making under risk helps noting many instances of such complex visible in the continuous flow of choices made in first person or observed in others, and interpreting them in the light of multiple spontaneous biases of judgement and reasoning discovered by psychologists, behavioural economists and cognitive neuroscientists. Knowing something about these issues does not seem to be a sufficient antidote against choices that, although not completely wrong, are often sub optimal, as they are driven by an excessive avoidance of risk or by the fear of exploring new routes. The strongest of these protective mechanisms is the so-called “loss aversion”, driving us to overestimate the negative consequences of a choice over the positive ones, and thus to prefer avoiding loss and failure over achieving gain and success. A reasonable precautionary strategy, one might say, at least until we wonder how many opportunities we might have lost while trying to avoid immediate losses, and, therefore, what we mean by “failure”. A few weeks ago I discussed this topic with some IUSS students, after asking them whether they felt they had achieved more successes or failures in their lives. Whatever the answer, I hope that was interpreted in the light of the topic of that class, and namely the ability to take advantage of experiences to improve one’s own expectations about the outcomes of choices. A “failure” would then become valuable information for specific brain networks underlying adaptive behavioural learning. And looking at the difficult times we live in, we might then wonder what our political institutions have learned from recent history, and what kinds of decisions could improve the fortunes of an increasingly complex and fragmented society. There might be many possible answers, but one of them includes them all: a long-term vision grounded in clear and attainable goals - provided they are pursued with the right effort - even if at the cost of some short-term loss. It might appear to be a trivial answer, and still this is something that we struggle to translate into concrete actions. Let us wonder, then, how much effort has gone into the scientific advances that allow us to take so many forms of well-being for granted today? It is not easy to maintain this kind of effort and motivation when it is only in the long run that the benefits come to outweigh the costs. And yet, it is only in a sufficiently broad time horizon, and not in the short-sighted choices that we often attend in our leaders’ decisions, that a path which is punctuated by failures as well, can lead to a few, yet great, relevant successes.

Find out who is Prof. Nicola Canessa

THE SPACE I LONG FOR

Andrea Taramelli, Geologist

“Innovation is not limited to its technologi-cal dimension but requires new visionaries”.

Since childhood one has been fascinated by what the concept of Space has always been: a vision toward the future full of uncertainties and ground-breaking discoveries. Throughout the previous century, and just at the beginning of this one, space has always played a key role in development and vision and saw one of its epic moments in January 1961, when John Kennedy was elected President of the United States. Within months of taking office, in May 1961 to be precise, Kennedy appeared before Congress and asked for support for an extraordinarily ambitious project. He said: “I believe this country must commit itself to the goal of putting a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth before the decade is out”. There has never been a space project so impressive for mankind or more important for space exploration, and none seemed so difficult or costly. A crazy but visionary project: a very expensive, dangerous voyage to get to the moon and back home. It was and is, in fact, widely believed that in an industrial society, the visionary view through technology is a decisive factor in maintaining an advantage over competitors and avoiding the loss of competitiveness of one's own industrial base and with it undermining national sovereignty itself, creating favourable conditions for downgrading, deindustrialisation and all the related socio-economic consequences. For this reason, the Apollo project cost a total of over 100 billion dollars today, involved hundreds of thousands of scientists and technicians and thousands of companies produced an enormity of technological innovations in many different industrial sectors and thousands of patents, and ensured the development of technological fields in which American industries have been undisputed leaders for decades.In September 1961, John Kennedy delivered a very famous speech at Rice University in Houston, near NASA headquarters, in which he announced the space programme in front of 40,000 people but did not see Neil Armstrong's moon landing because he was assassinated in 1963. For this very reason, however, before focusing exclusively on the concept of technology, trying to understand to what extent the latter constitutes an enabling factor for sustainable development, it is worth remembering how technological progress refers to the broader concept of innovation and development, not necessarily technological, and that these, rather than technology per se, are the foundation of all socio-economic progress, as happens in natural ecosystems with the process of evolution. We can therefore say that the space for economic and social welfare growth depends on a strong and strategic investment such as that of space, understood as that system that includes all the public and private actors involved in the provision of space products and services.

Space and what is now referred to as the New Space Economy is characterised by encompassing a long supply chain that starts from the manufacturers of space hardware (e.g. launchers, satellites, ground stations) to include the providers of enabling products (e.g. navigation equipment, satellite phones) and services (e.g.satellite-based weather services or direct-to-home video services). The importance of socio-economic development in the space sector nicely introduces the concept of "sustainable development," which takes into account the economic, social and environmental spheres that can ensure the needs of the current generation are met without compromising the needs of future generations. From a socio-economic perspective, development by itself is not sufficient; it must be planned and programmed in a sustainable way. It is important for this development to be durable over time and to be done in a gradual form, creating an economy based on an optimal relationship among economic growth, social conditions and resource use. In this way, the importance of the innovation space emerges as the main driver of a country's socioeconomic progress.

This strong investment in space through the New Space Economy must, therefore, now be aimed at exploiting the space infrastructure to the full, meaning not only existing capacities but also promoting and supporting research into innovative services and new technologies. To this, the need for direct research into new technologies and applications that better meet and indeed anticipate the most important contemporary societal challenges must be added. In this way, the importance of innovation as the main driver of a country's socio-economic progress emerges. This is the space I long for ... as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in the Oslo Manual: innovation is not exhausted in its technological dimension but needs new visionaries, as Kennedy was, capable of identifying a scale factor that can map the positioning of a given technology and the supply chain in which it is contextualised for the future of the next generations.

Find out who is Prof. Andrea Taramelli

THE ECONOMY (AND ECONOMICS) I LONG FOR

Alessandro Caiani, Economist

“My interest in economic studies arose from the experience of the global social movements at the turn of the century which aspired to a more equitable, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable development model”.

I stepped into adulthood during the turn of the century. Those were the years of the ICT revolution, witnessing the widespread adoption of computers, cell phones, and the exponential growth of the internet. It was also the time when the Euro came into being, border customs dissolved, and it seemed like a Europe without internal boundaries between states was taking shape. The onset of the new century carried the promise of a society where distances would vanish, uniting us all as citizens of a single "global village." All of this was made feasible by a societal and economic organizational model, which many believed to be the pinnacle of a millennial evolutionary process. Owing to its technological dynamism and the increasing international economic integration, it was expected to bring about widespread prosperity, laying the groundwork for lasting global peace. It was, allegedly, "the end of History".

Even in Economics, the prevailing belief was that the dominant paradigm had identified the correct recipes to solve the great problems of our societies. When I began my economic studies, the teaching reflected this monolithic vision. Economics provided the ideal model to which societies were to conform, elucidating how decisions made by hyper-rational individuals to maximize their personal gain almost always ensured, in a market economy, the most efficient use of resources and the achievement of maximum collective well-being. Thanks to the crystal-clear clarity of its mathematical architecture, Economics claimed autonomy and primacy over other social sciences. Historical, political, sociological, and behavioral aspects were almost completely excluded from the analysis. As a student, this was a source of immense frustration for me.

My interest in economic studies arose from the experience of the global social movements at the turn of the century which aspired to a more equitable, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable development model. Reading Ha-Joon Chang's criticisms of development policies, the analysis of welfare systems from the French Regulation School, or the critiques of market globalization by giants like Noam Chomsky and the "heretical orthodox" Joseph Stiglitz, with whom I later had the privilege to work, I fell in love with a kind of Economics, or Political Economy, that I struggled to find within my textbooks in University for a good part of my educational journey, I had to nurture my interests independently and parallel to my university studies.

Today, the situation is both different and similar to those times. Different, because the events of the last two decades have shown that History continues to unfold, sometimes revisiting dangerous chapters from the past. In Economics, the inability to confront major global economic crises and the mounting awareness of climate and environmental dangers have spurred the emergence of new areas of research: climate change economics, complexity economics, network analysis, experimental and behavioral economics are examples of rapidly expanding branches characterized by a multidisciplinary approach. Nonetheless, teaching still largely reflects the same monolithic approach of the past. The Economics I long for is instead a discipline that is genuinely pluralistic and open to interdisciplinary influences in both teaching and research.

At IUSS School, I found the ideal place to fulfill this aspiration. In my teaching activities, I am free to explore topics that typically do not find a place in standard university curricula. Not only do our students have the opportunity to delve into subjects and methodologies within their field of study, but they are also encouraged to engage with teachings in entirely different areas. In my research activity since I joined IUSS, I have investigated the impacts of climate change and green transition policies, collaborating with engineers, machine learning experts, and climate physicists, striving to amalgamate economic analysis methodologies with engineering impact models and predictive climate models, aiming to overcome the limitations of these three realms when taken in isolation. This cross-pollination is often challenging, and the outcomes uncertain, but at IUSS School, we firmly believe this is the most fruitful approach to tackle contemporary challenges, staying true to our motto: "Sapere Aude!" (Dare to Know!).

Find out who is Prof. Alessandro Caiani

THE CURE I LONG FOR

Annalisa Bonfiglio, Bioengineer

“The vision of more person-centered care is the positive perspective guiding the development of biomedical technologies and methodologies”.

My father used to tell me that when he was a child, the concierge doctors would come to see the patients, enter the room and, breathing in the air, would say, 'This one has pneumonia”. Of course, they had fewer means to fight pneumonia, and in the 1940s, you could still die because penicillin was not yet as widespread as it is today. However, it is undeniable that, in the space of a human lifetime, we have moved from a diagnosis still based on the (analogue) senses of the doctor to one based on the (digitalised) technology of machines, which are capable of measuring, with precision and repeatability, a large number of parameters. What awaits us tomorrow? We will grow old in a world where medicine has made giant strides in every direction: many diseases have been eradicated, and some decisively reduced. The “incurable illnesses” that were talked about in whispers until a few years ago may not have become curable, but in most cases, they have become problems that we can live with while having the means to maintain a reasonable quality of life. Although the reality is not without its chiaroscuros, we cannot but be globally proud of the advances in medicine and biomedical technology: no one would dream of going backwards. Diagnostics will lengthen the pace towards the early recognition of the first signs of disease, aided by technology that will become increasingly capillary and discreet. The advent of wearable technology, which until recently seemed more like a fad for Sunday sportspeople obsessed with the latest gadget, will make it possible to monitor our health day by day without almost noticing it. Like the black box for an aeroplane, we will have the opportunity to record in an imperceptible way (perhaps with a small tattoo in some invisible area of our body) thousands of signals produced by our body, and thanks to the artificial intelligence made possible by increasingly powerful computing machines, we will be able not only to monitor each one of them but also to correlate them, finding unexpected relationships, increasingly probative clues to a general state rich in all the nuances that make us a more or less healthy person, whatever that means. There is also food for thought here: what defines our ‘well-being’ is almost a misplaced question, one that is deeply rooted in what makes us who we are. The primordial question is another: what makes me the person I am? What differentiates me from my twin brother, who lived another life? It has only been 20 years since the completion of the sequencing of the human genome, long thought to be the Holy Grail of biology, but it is now clear that our true biological essence is more than the sequence of genes in our DNA and is made up of what we have lived, what we have eaten, even the education we have had. New data is added to what we will be able to detect with the powerful sensors we have at our disposal, and this data will serve to draw an ever more precise portrait of us, ever closer to who we really are, and this will be useful in drawing up an exact diagnosis, but a hypothesis of treatment that really fits our needs and takes all our characteristics into account in detail.

The vision of more person-centred care is the positive perspective guiding the development of biomedical technologies and methodologies today while at the same time giving an immediate perception of the complexity of the scientific, technical, managerial and ethical problems that will arise as this development becomes a reality.

Find out who is Prof.ssa Annalisa Bonfiglio

THE DOCTORAL PROGRAMME I LONG FOR

MARIO MARTINA Hydraulic engineer, PhD programme coordinator

“The PhD I long for is being built in Italy for hundreds of Italian and foreign researchers, with the support of the Ministry of University and Research”.

Once I finished university, I still had a great desire to study. Doing a PhD seemed like a great idea. I sent two applications. For one, I never received a reply; for the other one, after a few months, I stood before a committee asking me what research project I had. I had no clear project, but I was interested in the art of formulating questions and searching for answers. So, within a few weeks, my status changed from engineer to PhD student, and I immediately found myself facingsome difficulties. First, that of explaining that literally indefinite gerund to those who had not gone to university or had left it with a laurel wreath on their head. Then, that of fighting for my very existence. There were no rooms for PhD students in the department; their presence was tolerated in the corridors or the offices of shirker lecturers. Full of pride, leading a small group of peers yet perhaps just more nervous than me, I went to talk to the department director. I obtained the right to vacate the caretaker's former two-room apartment on the ground floor of the building to be used as a doctoral study room. Then I convinced the same caretaker to open an old storage room where I found desks, chairs and boards bound to be disposed of and to reuse them as furniture. I also convinced the computer technician to get the university's official e-mail. My existence as a PhD student and that of my colleagues was safe, but it was still three years of struggling for survival. Over twenty years later, what has changed? A lot, but not enough. MY perspective has certainly changed: I am now the coordinator of a PhD on sustainable development and climate change. It is a special doctorate, defined as being "of national interest' because it is offered by 52 Italian universities in agreement, over 50% of the total, and because it involves all academic disciplinary areas rather than one or two as in traditional courses. IUSS has been the promoter of this transdisciplinary PhD model - the first in Italy - because it is in its mission to experiment with training models that go beyond sectoral specialisation and that interpret the knowledge of the various academic disciplines as tools for the concrete solution of our society's problems. Our legal system recognises the PhD as the highest degree of education, a title that certifies high research, relational and management skills. I now have the responsibility, together with many colleagues, to ensure that the conditions are in place for our course to reach this goal. But despite the steps taken so far, I still see the struggle for the survival of doctoral students. Struggle for a professional identity and academic dignity. Even now, that indefinite gerund literally indicates a period of intolerable transition and uncertainty. And even after that, those who remain in academia must make further sacrifices and compromises before they can permanently make research their profession. Outside the academic world, in the world of business and public administration, there is still much to be done to give value to PhD titles.

The doctorate I long for would not have scholarships barely sufficient to pay for a room to rent, but work contracts with a decent salary on a par with other European states. The doctorate I long for would have bright spaces and adequate resources for one’s free exercise of curiosity. The doctorate I long for would be an apprenticeship in the art of formulating questions and seeking answers. The doctorate I long for would eventually be called a researcher, literally.

The PhD I long for is being built in Italy for hundreds of Italian and foreign researchers, with the support of the Ministry of University and Research, together with colleagues from 52 Italian universities who believe in and are committed to the ambitious and exciting PhD project in sustainable development and climate change.

Find out who is Prof. Mario Martina

LONGING FOR KNOWLEDGE

ANDREA SERENI, Philosopher

“Learning can only be achieved by initially constraining oneself to the paradigms and standards of a discipline”.

In a well-known essay from 1784, Immanuel Kant answers the question “What Is Enlightenment?”. The definition, as concise as it is iconic, is that “Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-imposed nonage”. This state of nonage, or immaturity is rooted in “the inability to use one's own understanding without another's guidance”, and it is self-imposed “if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one's own mind without another's guidance”.

It is not difficult to see in the passage from a state of immaturity to a state of maturity or intellectual adulthood of the human being a close analogy with the private microcosm of one's own life. After all, Kant points out, "It is so comfortable to be a minor". The personal revolution that awaits those entering academic studies often has - or should have - the flavour of Kantian enlightenment. The transition from student to scholar is a difficult but exciting conquest of freedom and autonomy, paved with obstacles and dead ends, with wide-open horizons and unsettling vastness. And with contradictions. Learning can only be achieved by initially constraining oneself to the paradigms and standards of a discipline, but growing is only possible through trespassing and blending, by pursuing curiosity and emancipation. Autonomy - the ability to orient oneself in thought – cannot be reached without guides, without relying on those who guard at least a small piece of knowledge to pass on, but requires such guidance not to become a strain or yoke, not to constrain diversity or limit inventiveness, not to inhibit confrontation, not to prevent what Kant considered "the most innocent of all that may be called 'freedom': freedom to make public use of one's reason in all matters".

The adventure of reason that animates the transition from minority to autonomy, from study to research and what, in uncertain and delicate times, it returns to individuals and society, is a complex mixture of trust and doubt, isolation and community, sharing and independence. It promises maturity but requires effort, exactitude and sensitivity. Above all, it requires courage. It is no coincidence that the motto - the very motto of the Enlightenment - which has long represented IUSS is the incitement with which Horace distils one of his most precious pieces of advice: Sapere aude - have the courage to use your own understanding.

To those who set out on this adventure, with the humility to learn and the passion for revolution, the only possible incitement is what remains of Horace's advice: incipe!

Find out who is Prof. Andrea Sereni

THE UNIVERSE I LONG FOR

Andrea Tiengo Astrophysicist

“All the sciences are making incredible progress, but only astrophysics can give us the big picture…stimulating us to reflect on how feeble the boundaries we have created on our tiny planet nd in our minds are”.

Astrophysics is a somewhat different science from the others because there is no possibility of interacting with what is being studied: what in other sciences are 'experiments' are 'observations' for astrophysicists. Indeed, if we exclude the Solar System, all astronomical objects are too distant to undergo any human influence. This passive condition can be somewhat frustrating, but at the same time reassuring: humanity may devastate its own planet, but a significant part of the Universe will remain unaffected, at least for a while... So, what is the point of talking about the Universe I long for ? No, it is not the ravings of a megalomaniac, as some may think. Nor can I wish that the Universe might spontaneously evolve into some particularly favorable form, at least on the timescale of our short lives. What does change at an incredible pace, however, is our knowledge of the Universe itself, thanks to the development of new technologies and the human capacity to use and interpret their results. Thirty years ago, I had just come of age and was in my final year of high school, which would lead me to my high school graduation exam and the (difficult but prompted by the irresistible allure of astrophysics) choice to enroll in a degree course in Physics. By early 1993, the Hubble Space Telescope was already operational, but it was only in December that its optics would be corrected, making it, until the recent launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (the main innovation of 2022, according to Science magazine), our sharpest eye on the Universe. Then, the discovery of the first planets outside the Solar System, around a neutron star, had just been announced. A neutron star is a stellar corpse that concentrates all the mass of a star larger than our Sun into a few kilometers. Two years later, the discovery of a planet orbiting a Sun-like star would follow, and since then, the number of known planets has now exceeded several thousand. The existence of planets around other stars has been imagined since the time of Giordano Bruno, but few had anticipated such a rapid explosion of knowledge in this area. Another unexpected discovery that occurred before the turn of the millennium was the evidence of an accelerated expansion of the Universe, confirming that dark energy and dark matter, so called precisely because we still do not know exactly what they are, make up more than 95% of the Universe. In more recent years, in 2015, the first gravitational waves were detected, produced by the merger of two black holes. We already had convincing evidence of the existence of both gravitational waves and black holes, but this single measurement, followed by dozens of similar signals, was the most direct confirmation. These discoveries were followed by gravitational waves produced by the merger of two neutron stars and the first image of a black hole, obtained in the radio wave band. Gravitational waves have opened a new window on the study of our Universe, adding to that of electromagnetic waves and particles of cosmic origin. But even these traditional windows on the cosmos have widened enormously in recent decades, mainly thanks to space missions that allow us to study the sky through radiations that cannot penetrate Earth’s atmosphere. This is especially true for X-rays, which I mainly focus on in my research. Among all cosmic X-ray sources, the main focus of my research is magnetars, neutron stars that host the most intense magnetic fields ever observed in the Universe. Again, their existence was unknown to us until recent times, as they were only hypothesized in 1992. Confirming how much these discoveries have affected our knowledge of the Universe, we can observe that in the last two decades, more than a quarter of the Nobel Prizes in Physics have been awarded in the field of astrophysics. This percentage is truly impressive, considering that the number of prizes awarded for these discoveries is the same as those distributed for astrophysics-related topics in the entire previous century. Our knowledge of the Universe is changing very rapidly, and I would like humanity to be fully aware of it: all sciences are making incredible progress, but only astrophysics can give us the big picture, helping us to look beyond our own backyard and stimulating us to reflect on how feeble the boundaries we have created on our tiny planet and in our minds are. Nowadays, there is even the possibility of disseminating scientific discoveries in an immediate and capillary manner and even involving, through new technologies, the citizenry in the process of analyzing and interpreting astronomical observations. This is the Universe I long for : an ongoing revelation of its secrets, inspiring as many people as possible.

Find out who is Prof. Andrea Tiengo

THE GRAMMAR I LONG FOR

MATTEO GRECO Linguist

“The grammar I long for… should be able to modify reality through mere words or phrases: it should allow us to unite two people by creating something new, a family, to unite one person to another by creating a community, and so on”.

The grammar I long for should be able to express infinite thoughts, without any restriction of number or type, from those that most closely mimic the reality around us to the most extravagant ones that no one has ever formulated before, like a beautiful purple camel wearing glasses and a red scarf wishing everyone Merry Christmas.The grammar I long for should be like the stars in the sky, a seemingly messy cluster of elements that reveal surprising regularities when looked at in the right way. It should make us all equal to the greatest and finest literati simply because it requires the same basic operations: Dante's Commedia would be as Divine as a shopping list or WhatsApp messages. The grammar I long for should be unique for all human beings, at least in substance, and allow only limited points of variation to be universal. We might not all understand each other instantly, but we would all speak the same language after all. In fact, in Nature, very small variations in the combinatorial mechanism acting on the same basic elements can give surprisingly different results, just as different as pencil leads can be from diamonds: same carbon atoms but different crystal structures. The grammar I long for should be easy to learn, not like when we, as adults, try to acquire a new language, but like when we learn to walk as children: maybe we fail a little, maybe we make a few mistakes when trying to use a subjunctive, but there is always a force within us capable of achieving results without excessive effort. The grammar I seek should allow everyone to express the same endless thoughts without dividing languages into 'a' and 'b' languages because of a (or rather of an apparently) different degree of complexity. Thus, the inhabitants of some parts of New Guinea or Hawaii who use little more than a dozen phonemes, or the speakers of Italian who use more or less thirty, could express the same ideas as some African populations with more than a hundred.

The grammar I long for should be able to modify reality through mere words or phrases: it should allow us to unite two people by creating something new, a family, to unite one person to another by creating a community, and so on.

The grammar I long for should allow us to refer to anyone and anything: from God to my 'self' via all the abstract and concrete realities in the world or our minds. It should allow the creation of new words to populate the fantastic worlds that adults and children like to imagine: in mine, you would find big elephants flying in the yellow sky with their sword-trunks alongside lions with feathered wings.

Actually, the grammar I long for is exactly the one that every human being uses in every single moment of his or her life when communicating, thinking, praying, saying the fateful 'yes', signing a contract, etc. In fact, thanks to the philosophical and scientific research that has accompanied the history of mankind and that has seen some major revolutions in the last 70 years, it has been realised that the most fundamental property of the grammar of human languages is exactly this: combining a few limited basic elements to obtain potentially infinite recursively generated structures. To take and adapt the example of pencils and diamonds, it is a bit as if the atoms themselves, the sounds of a language or the words themselves, combining in various ways, were able to create completely different crystal structures. Thus, it does not matter how many bricks there are, to begin with, since what matters is the combinatorial capacity whose result is always infinite. It was also realised that apparently very different languages, such as Italian and Japanese, share the same basic principles and appear as distinct sides of the same coin.

Find out who is Dott. Matteo Greco

THE SAFETY I LONG FOR

GERARD O’REILLY Structural Engineer

“We can never eliminate risks but we must under-stand them as much as current knowledge allows us to. We also need to know and improve our capabilities in order to address and mitigate them”.

When I was young and used to do many odd jobs around the house with my father, I learned countless practical skills. Obviously, it was a moment of great joy for him to see his son become an engineer, as it is for many. I was finally going to go and built the next great works. Me, with the shovel in hand, ready to place the concrete for the first column.

It may be somewhat strange initially to speak about civil engineering and advanced mathematics, theory that would give you a headache at first (but mind-blowing once grasped), in addition to the countless methods of numerical simulation and analysis. What is all this for? Our safety. We don’t put steel bars in concrete because we like it but because it is needed. It is needed to give us robust and safe structures.

During the pandemic, a phrase that you heard often was “to guarantee your safety”. Taking nothing away from the objectives of those who said it, as it was a surreal and painful period for many, but for those who deal with risk and safety, it may have drawn a wry smile. Nothing is for certain and nobody can guarantee you anything. What we can do is understand the problem with the principles we have learned and manage and mitigate the risk to an acceptable level, that we deem safe enough – bingo!

Risks are all around us. Every time we drive a car, there is a risk of us crashing or that the car may spontaneously burst into flames. We understand these risks but take the appropriate measures to minimize them: insurance, car inspections, driver licences.

“Ah but in a few years, computers will do everything” they say. Sure, we can’t deny that computers and computational power have revolutionised our world. Some jobs will become obsolete and automated, but new frontiers will open. In the face of a challenge, there is always opportunity, and now we find ourselves in this moment of opportunity.

It is exactly this approach we take into the field of engineering research. If we live in a seismically-prone region, have we placed enough reinforcement to ensure our house is sufficiently safe from collapse? Or rather, that the risk of it collapsing is acceptably low? If we have strong thunderstorms and floods, do our infrastructure networks have the capacity to withstand such impacts? Is the risk of major disruption due to a single element sufficiently low? Have we applied our knowledge of complex theory and numerical simulation potential to fully understand the hazards we face and deal with them? For example, less than 100 years ago, little was understood about the dynamic response of structures to earthquakes and how best to face this problem. Immense progress has been made in this regard, but there is inevitably much yet to do.

We must face this challenge head-on. We can never eliminate risks but we can understand them as far as science allows. We must also be sure of our own knowledge to adequately face and mitigate them. As the wise master Sun Tzu once said: “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles”. It is precisely this that allows us to have the safety that we desire.

Find out who is Dott. Gerard O'Reilly

THE MATHEMATICS I LONG FOR

SILVIA DE TOFFOLI Philosopher

“Sometimes you do not understand anything, be-cause mathematics is difficult. Then we must have patience and not be afraid of not understanding... our way and with our own time. And above all, we must not be afraid of making mistakes”.

During my Erasmus Exchange in Paris as an undergraduate, I was exploring new areas of mathematics, and life. In the first topology class, our professor told us to buy colored markers. We were surprised. The mathematics I was used to doing was in black and white, and I had always only needed a pen. Instead, the mathematics I learned in Paris was colorful. This is the mathematics I long for. It's a fun kind of mathematics but no less rigorous; on the contrary, it is authentic and understandable and forces us to learn to see more clearly. Henri Poincaré used to say that the most important task of those who teach mathematics is to develop the students’ intuition. Intuition, in fact, is not something one is born with but something one cultivates. It is developed using colored markers to solve topology problems by drawing, making mistakes, and redrawing. One of the most significant aspects of doing mathematics is that we do it. This sounds like a triviality, but it is not. In other sciences, we must trust the people who did experiments and the accuracy of the data in books or articles. In mathematics, we do not have to trust anyone or accept external authority; we just have to learn to think for ourselves. And we can all do that. Sure, we have to start somewhere, but then whether a theorem is really a theorem is something we can in principle ascertain for ourselves.

Sometimes we do not understand anything because mathematics is difficult. But then we must be patient and have the courage to learn to understand in our own way and in our own time. And above all, we must not be afraid to be wrong. Contrary to what is too often thought, mathematicians make plenty of mistakes. They make mistakes all the time. But they also learn from their mistakes; with experience, they learn to use their mistakes creatively. We can therefore make mistakes too.

The mathematics I long for is inclusive in that it embraces many ways of reasoning. Some enjoy solving algebraic problems by manipulating formulae, others would like to find refuge from formulae as soon as possible, but perhaps they love art and if they were introduced to geometry, they would love that too. The mathematics I long for is not a monolithic block but a bouquet of flowers from which everyone can extract the ones whose smell seduces them most and whose color suits them best. And what I long for is also a different image of mathematics. Many people are intimidated by mathematics - but that is because they have a vague and limited idea of the discipline. And even the philosophy of mathematics has almost always regarded mathematics as a domain of immutable truths inaccessible to most. But is this really the case? Investigating the different facets of mathematical practice, such as those where we use colored markers and make mistakes but then also manage to solve concrete problems, forces us to look at mathematics as a human activity rather than a domain of inaccessible truths. Unveiling the human side of mathematics makes it more chaotic, yes, but also more accessible, more colorful, and sexier. So, let us set aside this frigid monochromatic mathematics (which was never really mathematics, but only an image that, unfortunately, many still hold on to) and open our eyes to this colorful mathematical world.

And then, as Brouwer said, mathematics is a kind of internal architecture. It is something we do, but at the same time, it shapes us, in the sense that by doing mathematics, we create who we are; we forge character, so to speak. Mathematics is a discipline of thought that sharpens the mind.

The mathematics I long for s messy, and sometimes difficult (but all the really important things are difficult), but it is also inclusive, authentic, and, above all, colorful. It is an amazing kind of mathematics!

Find out who is Dott.ssa Silvia De Toffoli

THE CLIMATE I LONG FOR

GIORGIA FOSSER Climate analyst

“I chose IUSS School because I found colleagues who, in addition to their abilities, put their heart into it... because it is right, morally right, to do something for our world”.

It was a gloomy winter day when I was asked to write these lines on the climate I long for. I immediately thought of the sun, the sea and the serenity of my university days when the heat was not frightening and a downpour only brought coolness... this is no longer the case.

But let's start the story from the beginning... When I was in university, climate change was not yet talked about, or at any rate, it was not an issue that was discussed while having a spritz celebrating the success of an exam. Yes, there had been the particularly hot summers of 2003 and 2006, but we just took advantage of the sea and that was it. I would have never thought that our climate would change so drastically, and that I had been contributing to this change as well. Then, by chance, I ended up working on climate and climate change with my doctorate in Germany and, a little less causally, I had a son. Watching him growing up, I started thinking about his future and the climate I would have liked him to experience, like the one I had experienced, without fears of not having enough water, of being swept away by a glacier snowmelt or an overflowing river by a water bomb. I was angry that the stupidity, narrow-mindedness and miserable interests of men and women prevented my son, all of our children, from enjoying our fantastic Nature, as we did, but without taking advantage of it, as we did. In this, I found the motivation for my work, to understand the changing climate and how we can adapt to these changes that are unfortunately unavoidable. I have worked on these issues in Holland, Germany, France and the United Kingdom, but I returned to Italy to work at IUSS. I came back because at IUSS, I found an exceptional working environment, with people who care for others and care about the issues of climate and its social impacts. I chose IUSS because I found colleagues who, in addition to their skills, put their hearts into it, not just to publish an article or make a career, but because it is right, morally right, to do something for our world. I am at IUSS because there is a young group of climate physicists, engineers, economists, philosophers, neuroscientists and linguists united by the desire to share their sectoral knowledge and skills and integrate the latter to tackle the issue of climate change more effectively. At IUSS, we are like a small medical team that does its best to take care of our ailing climate and raise awareness among young, and even less young, people about this problem which, whether you may like it or not, affects everyone... We are all working to achieve the climate I would like.

I wish climate and weather events did not frighten us. I would like us to learn to respect our nature, which above all, allows us to live. I would like us to learn not to be blind and deaf to climate change. I would like climate change not to be just a problem among others or a problem to others. I would like people, and researchers first, to challenge themselves beyond their specific field of knowledge to find new interdisciplinary solutions to deal with a changing climate in an evolving world. I would like everyone to have the opportunity to experience the climate that I breathe every day working at IUSS with a young, dynamic, enterprising group that is confident that, together, positive changes are possible. I work at IUSS for the climate I long for, do you?

Find out who is Dott.ssa Giorgia Fosser

THE UNIVERSITY I LONG FOR

Lorenzo Bianchi Chignoli, student

The University is a fascinating institution, proudly medieval in its history and rituals, driving development and aiming for the future by steering technological, scientific, and cultural progress. Especially since the 1960s, opening its doors to the masses, it has also become a social laboratory: the long-dreamed republic of letters. Yet, there is still a long way to go for the University to fulfill its potential and enormous ambition to become the engine of social integration.

Since the 1990s, Italy has witnessed a continuous increase in inequalities. We are the country with the highest number of NEETs – young people who are not studying, working, or seeking employment. Furthermore, we rank third to last in Europe in terms of the percentage of enrolled students at the University. Unable to insinuate that there is an innate aversion to studies in Italy, there must be other obstacles – social, economic, cultural – making their appearance in individuals' lives. And it is tremendously difficult to identify these hidden barriers that subtly limit social mobility and the expression of individual capabilities.

In the past, social class, income, and private connections explicitly determined the fate of individuals in terms of education and career. Over time, individual abilities have increasingly made a difference in people's lives compared to genealogy. The fundamental idea of rewarding merit has prevailed: a hopeful bet on what an individual is willing to do for society, weighed on their abilities as much as on their determination, and inversely proportional to the obstacles that have held them back until that point.

However, merit is not a private property, even though it is discussed as an individual characteristic. Merit is largely a normative, not descriptive, ideal. And individual capabilities, whether received at birth or matured through state care, must always be put in the service of the community. It is on this costly neglect that delays in the most urgent needs of our time are based: climate change, social equality, and civil progress.

In short, we have not completely shaken off the age of privileges and, especially, of the disadvantaged. Attending university in Italy today can no longer be simply a temporary stage in a biography or an investment in education to aspire to a life of rentiers. Instead, studying must be a mission carried out for the benefit of the entire community: neighbors and distant ones, similar and different; in support of decision-makers but always aiding the last and the invisible.

The strong need for real knowledge is expressed in the growing dissatisfaction with abstract ideas of study and research, leading us towards a university where knowledge makes sense only when it benefits the widest number of people. Freeing ourselves from the prejudice that this cannot apply to pure disciplines. Shedding the charm of salon and armchair culture; of the hermitic, and perhaps ultimately vainglorious, intellectual. Without romanticism, but with realism: who can take universalism to heart in the race for well-being if not those who dedicate their lives to knowledge?

At IUSS, everyone seems to be aware of holding a somewhat microscopic position but part of an epochal humanitarian purpose. Linguistics, law, philosophy of mind, neuroscience, are the keys with which to remedy the distortions – increasingly detailed but equally decisive – of a small portion of the world. Research is our immediate grasp on it, and the proof of everyone's commitment to each other's lives.

For a IUSS student, even the funding for education takes on the value of an investiture. It is the imprimatur of a School and a State that entrust us with a mission and ask us not to be disappointed. They reward merit, reminding us that neither income nor social background matters to become what we want. At the same time, however, they remind us that we possess merit without being its owners.

THE SOCIETY I LONG FOR

RICCARDO PIETRABISSA Rector

“In the society I long for, doctors and historians, engineers and economists, mathematicians and philosophers, chemists and art historians, linguists and biologists... must have a common language”.

I have always thought and hoped that I could contribute to the progress of society, which is not only determined by material wealth but rather by the ability of people to understand the consequences of their decisions and to be able to choose the best ones. It is therefore necessary to have people in society who are competent, often in a variety of fields, and who share the values of the community. These qualities must belong at least to decision-makers in politics, public administration, the professions, industry and finance, and culture.

When I enrolled in engineering, I wished to design engines, cars, and aeroplanes. Just the thought of being able to make a new vehicle that worked better than its predecessors, that was faster, that consumed less, that looked better, that had new functions was an exhilarating ambition for me. And so, I first studied the mathematics, physics and chemistry necessary to have the basic elements to calculate how to achieve certain performances in a design, then the different mechanical, electrical, electronic, material technologies with which to transform matter to obtain objects and devices with new functions.

More than forty years have passed since then and technology has changed dramatically. Today cars are more and more electrically powered , they are controlled by computers that did not exist then; today we normally make phone calls while driving and take photographs with our mobile phones; today our wristwatch tells us where we are and how to get from one place to another; today many of the things I studied at university are no longer needed, some no longer exist except in the history books of technology. Science adds knowledge, technology changes its paradigms. Even societies retain their values, but their impact on social and economic life changes.

Our parents could not have imagined today’s world, even though they contributed to it. We have to ask ourselves how many have consciously participated in the changes of the last thirty years, how many have made decisions aware of the transformations they would bring about, how predictable the direct and indirect effects of decisions are, and the immediate and long-term effects.

New graduates and research doctors can no longer be experts only in the disciplines of their courses of study, especially if they will have decision-making roles in society. In the society I long for, doctors and historians, engineers and economists, mathematicians and philosophers, chemists and art historians, linguists and biologists must be able to participate in the progress of society by understanding each other; they must have a common language.

The decomposition of knowledge, problems and nature through man-made disciplines must be harmonised to achieve the quality of progress, what many call sustainable development.

At IUSS we educate students in complex thinking, in the integration of knowledge, in the cultural innovation that must become the preparation of those who will decide the future of the next generations. This is the society I long for .

Find out who is Prof. Riccardo Pietrabissa